If you’ve ever stepped into a gym or nutrition store, you’ve likely encountered BCAA supplements promising bigger muscles, faster recovery, and better athletic performance. But how do BCAA supplements work in reality? The truth is far more nuanced than supplement labels suggest. While BCAAs do play legitimate roles in muscle metabolism, scientific evidence reveals significant limitations in their effectiveness when taken alone. Research spanning decades—including human intravenous infusion studies—paints a picture that challenges many popular assumptions about these supplements. This article cuts through the marketing hype to explain exactly what happens at the cellular level when you take BCAAs and when they might actually deliver benefits.

Understanding BCAA supplementation requires examining the biochemistry behind muscle protein synthesis and why consuming just three amino acids often fails to deliver promised results. The evidence shows that while BCAAs activate certain signaling pathways, their effectiveness is fundamentally constrained by human physiology in ways most marketing materials ignore.

What Are BCAAs and Why They’re Different From Other Amino Acids

Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) comprise three essential amino acids—leucine, valine, and isoleucine—that your body cannot produce independently. Unlike most amino acids processed in the liver first, BCAAs bypass hepatic metabolism and travel directly to skeletal muscle tissue for oxidation. This unique metabolic pathway initially sparked interest in their potential as anabolic agents more than 35 years ago, when rat studies suggested BCAAs might be rate-limiting for muscle protein synthesis.

However, critical differences between rat and human physiology undermine these early findings. Rat skeletal muscle represents a much smaller percentage of total body mass compared to humans, and regulatory mechanisms for muscle protein synthesis differ substantially between species. Most animal studies also employed the “flooding dose” technique—measuring tracer incorporation over extremely brief windows that couldn’t distinguish between transient and sustained effects. These methodological differences created a foundation of evidence difficult to translate to human applications.

The Muscle Protein Synthesis Process Explained Simply

Your muscles exist in constant flux—existing proteins break down while new proteins synthesize to replace them. For new muscle protein to form, all nine essential amino acids must be present simultaneously in adequate quantities. Your body can produce eleven non-essential amino acids internally, but the essential ones must come from your diet. This creates a fundamental constraint: muscle protein synthesis cannot proceed if even one essential amino acid is unavailable, regardless of how much of the others you consume.

Following a protein-containing meal, your digestive system breaks down dietary protein into amino acids that enter your bloodstream. During this post-prandial state, plasma amino acid concentrations rise, providing abundant precursors for muscle protein synthesis. Under these conditions, your muscles enter an anabolic state where synthesis exceeds breakdown. However, several hours after eating, amino acid levels fall as absorption ceases. Your body transitions to a catabolic state where muscle protein breakdown actually releases amino acids into circulation rather than taking them up—effectively turning your muscle tissue into a reservoir for the rest of your body.

Why BCAAs Alone Can’t Maximize Muscle Growth

When you consume BCAAs in isolation—without the other six essential amino acids—the only source of those missing essential amino acids is intracellular pools derived from muscle protein breakdown. Given that muscle protein breakdown already exceeds synthesis by approximately 30% in normal post-absorptive humans, you begin in a catabolic state.

Consider what happens when you take a BCAA supplement: you flood your system with three essential amino acids, but the other six required for complete muscle protein remain available only through ongoing breakdown of muscle tissue. Even under the most generous assumptions—that BCAA consumption improves recycling efficiency of essential amino acids by 50%—the math reveals minimal benefit. This would translate to roughly a 15% increase in muscle protein synthesis rate, shifting the fractional synthetic rate from approximately 0.050% per hour to 0.057% per hour—a difference so small it would be extremely difficult to measure clinically.

Your body cannot produce essential amino acids internally, and without dietary sources, the rate-limiting step for protein synthesis becomes availability of the six essential amino acids not provided by BCAA supplementation. This biochemical reality means that BCAAs alone, regardless of dose, cannot create conditions necessary for meaningful muscle protein synthesis stimulation.

What Human Research Reveals About BCAA Effects

The most direct evidence comes from intravenous infusion studies, which allow precise control over amino acid delivery. In a landmark study, researchers infused a BCAA mixture into ten post-absorptive subjects for three hours while measuring muscle responses. The BCAA infusion increased plasma concentrations of all three BCAAs four-fold while simultaneously decreasing concentrations of other essential amino acids. Rather than stimulating muscle protein synthesis, the infusion produced a significant decrease from 37 to 21 nmol/min/100 ml leg.

A subsequent 16-hour infusion study extended these observations. Despite achieving BCAA concentrations five to eight times baseline—potentially double what oral supplementation produces—muscle protein synthesis decreased from 36 to 27 nmol/min/100 ml during the infusion period. Muscle protein breakdown also reduced, meaning overall muscle protein turnover decreased while the catabolic state continued. These findings lead to an inescapable conclusion: BCAA infusion not only fails to increase muscle protein synthesis in humans but actually reduces it.

How BCAA Signaling Works (And Why It’s Not Enough)

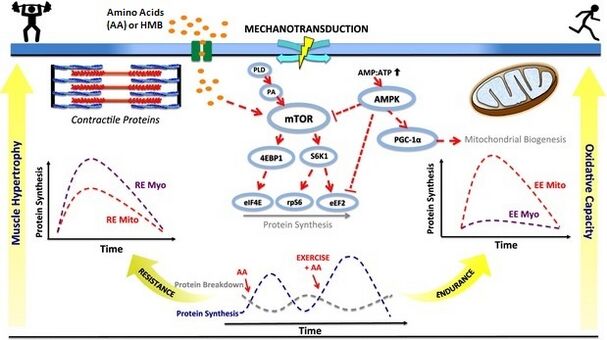

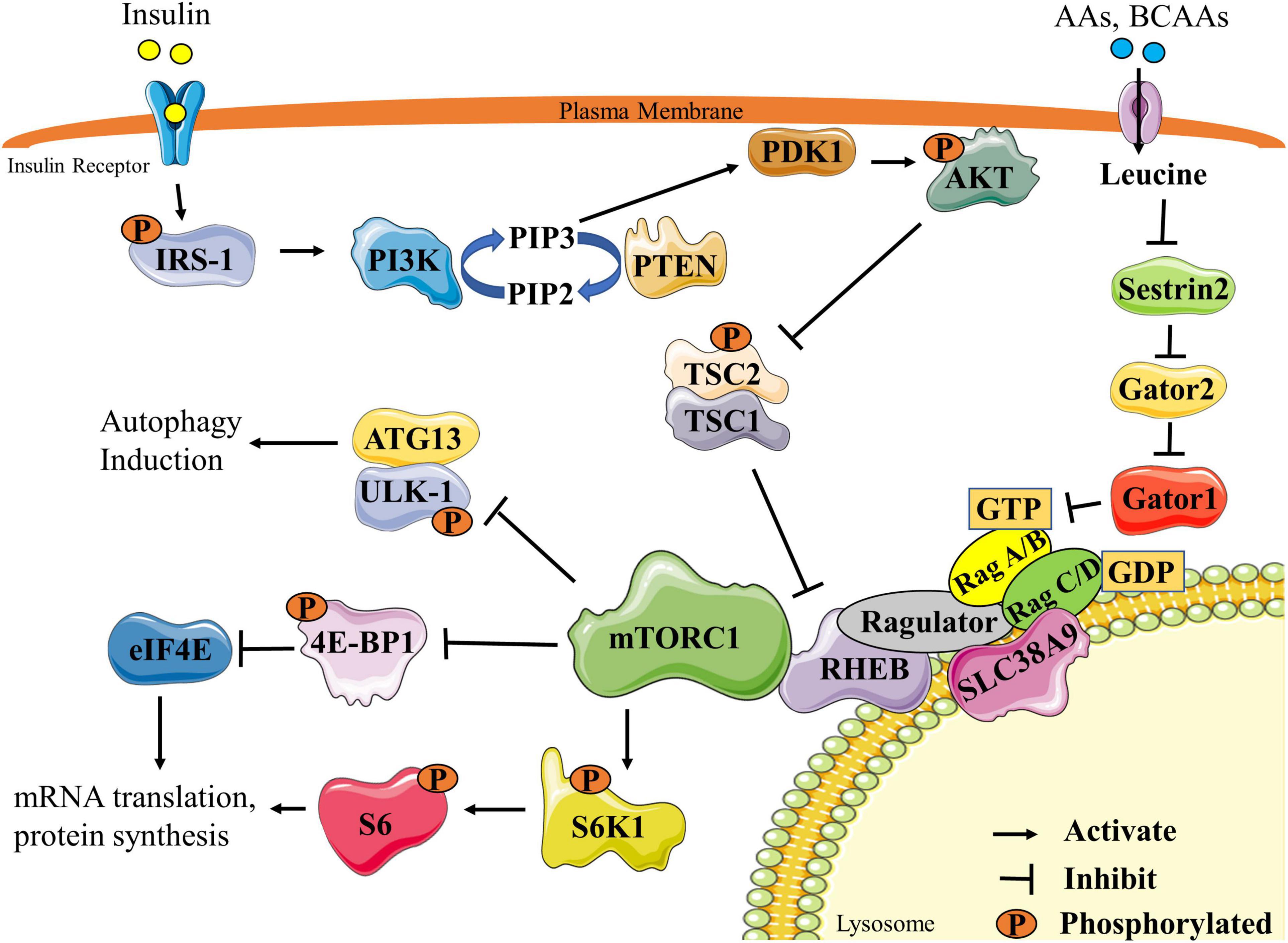

Proponents often point to activation of intracellular anabolic signaling pathways as evidence of BCAA effectiveness. When BCAAs enter muscle cells, they trigger phosphorylation events involving key factors such as mTOR, S6 kinase, and 4E–BP1—molecules that regulate protein synthesis initiation. The logic follows that increased signaling activity should translate to increased muscle protein synthesis.

However, this reasoning overlooks a critical requirement: signaling pathway activation can only coincide with increased protein synthesis when ample essential amino acids exist to provide necessary precursors. A dissociation between signaling factor phosphorylation and actual muscle protein synthesis has been demonstrated repeatedly when essential amino acid availability becomes limited. For instance, increasing insulin concentration through glucose intake potently activates anabolic signaling pathways, yet this fails to increase muscle protein synthesis when essential amino acids remain scarce.

The intravenous BCAA studies demonstrate this principle clearly. The massive BCAA concentrations achieved during infusion would reasonably activate signaling factors, yet muscle protein synthesis decreased because essential amino acid availability dropped due to reduced protein breakdown. These results prove that availability of all essential amino acids—not signaling factor activity—represents the rate-limiting control of basal muscle protein synthesis.

Individual BCAA Roles: Leucine vs. Valine vs. Isoleucine

While most research examines BCAA mixtures, the individual amino acids may produce different effects. Evidence suggests that leucine alone might exert an anabolic response, while comparable data doesn’t exist for isoleucine or valine. This observation has led to speculation that isolated leucine supplementation could prove more effective than BCAA combinations.

Two significant limitations constrain leucine’s effectiveness when taken alone. First, the same availability issues affecting BCAA mixtures also apply to leucine alone—without adequate supplies of all essential amino acids, protein synthesis cannot proceed regardless of signaling pathway activation. Second, elevating plasma leucine concentration activates the metabolic pathway that oxidizes all BCAAs. When leucine is consumed alone, plasma concentrations of both valine and isoleucine decrease, potentially making these amino acids rate-limiting for muscle protein synthesis.

BCAAs also compete with each other for transport into muscle cells. All three share the same active transport system, meaning they compete with each other for cellular entry. If leucine is rate-limiting for protein synthesis, adding the other two BCAAs might actually limit stimulation because of reduced leucine entry into cells.

BCAA Effects When Combined With Protein

The effects of BCAAs change dramatically when consumed alongside complete protein sources. One study found that 5 grams of BCAAs added to 6.25 grams of whey protein increased muscle protein synthesis to levels comparable to 25 grams of whey protein alone. This finding suggests that one or more BCAAs might be rate-limiting for the muscle protein synthesis response to whey protein.

This result highlights that BCAA effects in conjunction with complete protein represent a fundamentally different scenario than BCAAs alone, since intact protein provides all essential amino acids necessary for complete protein production. The enhanced effect likely stems from combining complete amino acid availability with the potent signaling properties of leucine in particular. For individuals struggling to consume adequate protein, this finding suggests BCAAs might enhance the muscle-building potential of smaller protein meals.

Performance, Recovery, and Practical Benefits

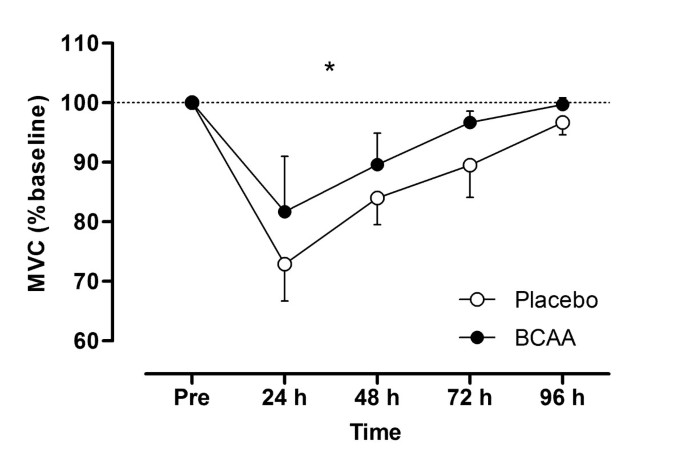

Systematic reviews examining BCAA supplementation in athletic populations reveal that while these supplements tend to activate anabolic signals, actual performance and body composition benefits prove negligible. Studies across various sports consistently show trivial effects on performance measures regardless of supplementation protocol length or dosage.

The effects on muscle soreness and recovery present a more encouraging but still mixed picture:

- In endurance sports, results remain inconsistent across studies

- Some research found reduced ratings of perceived exertion in BCAA groups among endurance cyclists

- Muscle soreness was lower in BCAA groups compared to placebo among distance runners

- Studies involving resistance training participants consistently indicated benefits for attenuating muscle soreness

- Multiple studies reported BCAA consumption preserved performance following muscle-damaging protocols

These findings suggest that resistance athletes may derive more consistent recovery benefits from BCAA supplementation than endurance athletes.

Safety Profile and Who Should Use Caution

BCAA supplementation is generally considered safe for healthy individuals when consumed at recommended doses (5-20 grams daily). The most common side effects reported include mild gastrointestinal discomfort, fatigue, and headache, though these occur infrequently.

Certain populations should exercise caution:

- Individuals with maple syrup urine disease must avoid these supplements completely

- People with ALS should consult healthcare providers before using BCAAs

- Those managing diabetes or hypoglycemia should monitor blood sugar responses

- Long-term safety data remains limited, as most studies examined effects over weeks to months

Practical Recommendations for Athletes

The weight of scientific evidence suggests that BCAA supplementation alone is unlikely to produce meaningful increases in muscle mass or athletic performance in individuals consuming adequate dietary protein. Athletes already meeting protein recommendations through whole food sources will probably find additional BCAAs provide minimal incremental benefit.

BCAAs might actually matter in three specific scenarios:

- As an addition to suboptimal protein doses (5g BCAAs + 6.25g whey ≈ 25g whey)

- For reducing muscle soreness in resistance-trained individuals

- Supporting immune function during intensive training periods

For athletes concerned about immune function, research shows BCAA supplementation helped maintain plasma glutamine levels that decreased significantly in placebo groups after competition. This suggests a potential role for BCAAs in supporting immune function during periods of physiological stress.

The practical implication is clear: prioritize meeting total protein recommendations through whole food sources or complete protein supplements rather than relying on BCAA supplementation for muscle building. BCAAs may have specific applications but cannot substitute for adequate protein intake. Those who choose to use BCAA supplements will find they are generally safe but unlikely to provide substantial benefits beyond proper nutrition and training program design.